Cache-Warming

Introduction

In High-Frequency Trading (HFT), minimizing memory access time is crucial for optimizing the responsiveness of programs, which is crucial in HFT where even few nanoseconds can make an impact in trading. One effective technique to achieve this is cache warming. Cache warming involves preloading data into the CPU cache before it is actually needed, thereby reducing the time required for memory accesses during execution. This article explores the concept of cache warming in the context of C++, its benefits, and practical implementation strategies.

Understanding CPU Caches

What is a CPU Cache?

A CPU cache is a smaller, faster memory located closer to the CPU core that stores copies of frequently accessed data from the main memory (RAM). Modern CPUs typically have multiple levels of cache (L1, L2, and L3) with varying sizes and speeds:

- L1 Cache: The smallest and fastest, located closest to the CPU cores, often split into two parts: Instruction Cache (L1i) and Data Cache (L1d). It holds the most frequently accessed instructions and data to speed up processing. The size of L1 cache usually ranges from 2KB to 128KB, but is usually as 64KB in modern processors.

- L2 Cache: Larger and slightly slower than L1 cache, but still significantly faster than the main memory. This cache is either dedicated to each CPU core. It serves as a secondary level to store frequently accessed data and instructions that do not fit in L1. The size of L2 cache usually ranges from 128KB to 1MB.

- L3 Cache: The largest and slowest among the cache levels, shared among multiple cores. This cache is located outside the CPU and is shared by all cores. It is slowest of the three levels but still significantly faster than main memory (RAM). It helps coordinate and speed up data sharing among cores. Its size usually ranges from a few megabytes to tens of megabytes.

The hierarchy and proximity of these caches to the CPU cores mean that accessing data in the L1 cache is much faster than accessing data in the L2 or L3 caches, and significantly faster than accessing the main memory. Efficient use of these caches can drastically improve the performance and responsiveness of a program.

Cache Warming

What is Cache Warming?

Cache warming involves preloading data into the CPU cache to ensure that it is readily available when required by the program. This reduces the latency associated with fetching data from the main memory, which is significantly slower compared to accessing data from the cache.

Benefits of Cache Warming are below

- Reduced Memory Access Time: Preloading data into the cache minimizes the time the CPU spends waiting for data from the main memory.

- Improved Program Responsiveness: With essential data already in the cache, the program can execute more smoothly and respond faster to user inputs.

- Higher Throughput: Increases the throughput of applications by reducing the number of cache misses and memory stalls.

Implementing Cache Warming in C++

One common technique for cache warming in C++ is prefetching. Prefetching involves loading data into the cache before it is needed. C++ provides several ways to implement prefetching. We will discuss two primary ones below

- Using Compiler Intrinsics - Most modern compilers provide intrinsics for prefetching data into the cache. For example, GCC provides the __builtin_prefetch function or we can use _mm_prefetch which explicitly takes 2nd arguments as int which identifies in which cache level do we need to fetch the mentioned data. Below is the code example

//Using compiler intrinsic prefetch

void matrix_mulitply (

const std::vector<std::vector<int>> &first,

const std::vector<std::vector<int>> &second,

std::vector<std::vector<int>> &product) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

for (int k = 0; k < N; ++k) {

_mm_prefetch(&second[k][0], _MM_HINT_T0); // Prefetching second matrix

for (int j = 0; j < N; ++j) {

product[i][j] += first[i][k] * second[k][j];

}

}

}

}

In this example, _mm_prefetch is used to prefetch matrix second[k][0] location into the cache with a hint that the data will be accessed soon.

- Software Prefetching - Manual prefetching can also be implemented by structuring code in a way that hints the hardware to load data into the cache. Code Example:

//Using software prefetch

void matrix_mulitply(

const std::vector<std::vector<int>> &first,

const std::vector<std::vector<int>> &second,

std::vector<std::vector<int>> &product) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

for (int k = 0; k < N; ++k) {

volatile int temp = second[k][0]; // Prefetching second matrix

(void) temp; // Prevents compiler optimization

for (int j = 0; j < N; ++j) {

product[i][j] += first[i][k] * second[k][j];

}

}

}

}

In this example, volatile int temp variable is used to prefetch matrix second[k][0] location into the cache for further computations. This reduces the latency of subsequent memory accesses, hence improving overall performance.

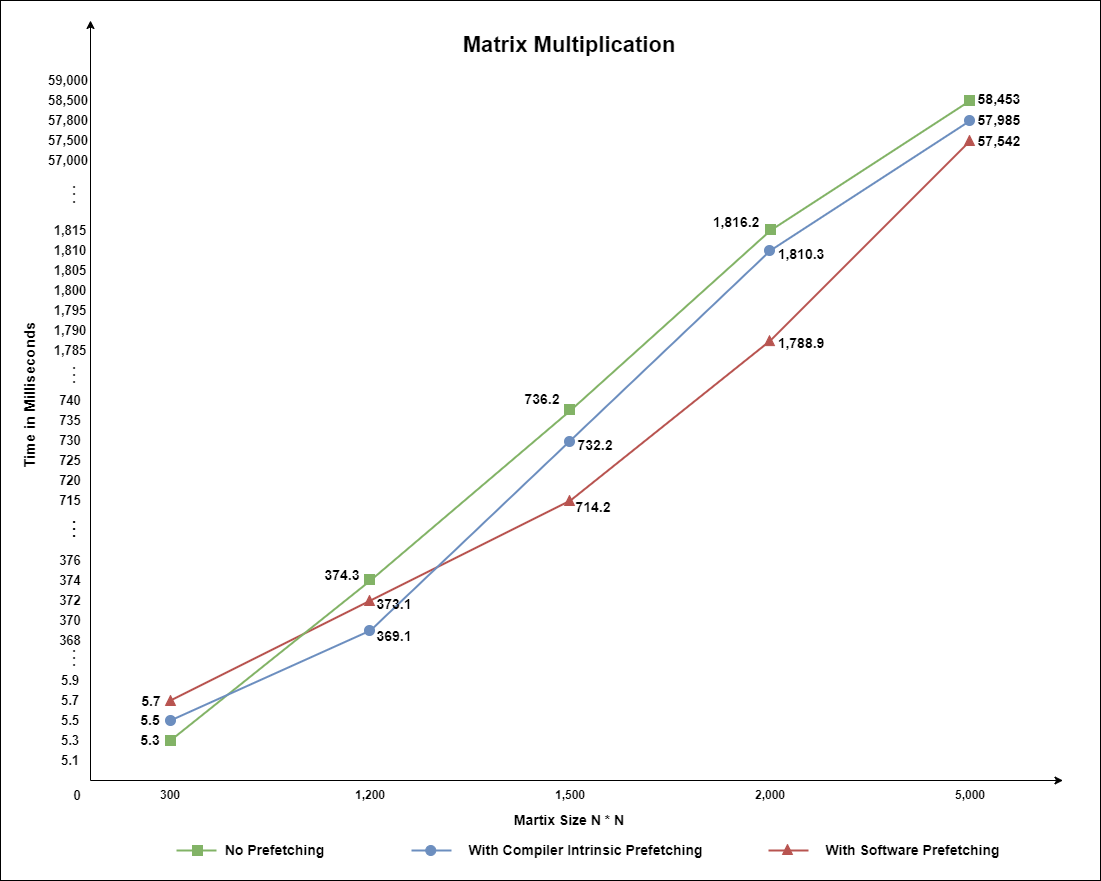

Note: This observation is recorded on machine with clock speed: 2800MHz, L1 cache size: 32KB, L2 cache: 4MB, L3 cache: 16MB

The observations reveal that using cache warming techniques, specifically compiler intrinsic prefetching and software prefetching, can significantly improve the performance of a C++ program by reducing memory access times. Compiler intrinsic prefetching consistently provides performance gains, with notable reductions in execution times across various data sizes, particularly as the data size increases. Software prefetching also improves performance but not as effectively as compiler intrinsic prefetching in the observed cases. Other alternatives to consider include hardware prefetching, loop restructuring to improve data locality, and utilizing cache-friendly data structures. The effectiveness of these techniques can vary depending on the specific hardware and application, highlighting the importance of testing and profiling on the target machine to determine the optimal prefetching strategy.

Use in HFT

To illustrate cache warming, let’s compare two versions of a C++ program: one without cache warming and one with cache warming. Both versions simulate a stock trading system where orders are placed based on tick data.

Without Cache-Warming

struct Instrument {

int orderCount;

};

bool shouldBuyStock(TickData &data) {

// Logic for purchasing stock

}

void placeOrder(TickData &tickData, Instrument **&instList, bool warmUp) {

// Logic for placing order

instList[tickData.instrumentId]->orderCount++;

}

//Receives market tick data and makes a trading decision

void onData(TickData &tickData) {

if (shouldBuyStock(tickData)) {

placeOrder(tickData, instrumentList, false);

}

}Over here, on each tick data update when we need to access an instrument, if the instrument data is not in the cache, a cache miss occurs. The CPU then fetches the data from the slower main memory, leading to delays. If we call placeOrder even when no order is placed (else branch), the program preloads the instrument data into the cache. This reduces the likelihood of cache misses when the actual order needs to be placed i.e. critical path of the code needs to be executed. So, we can optimize the code in following way:

With Cache-Warming

struct Instrument {

int orderCount[2];

};

bool shouldBuyStock(TickData &data) {

// Logic for purchasing stock

}

void placeOrder(TickData &tickData, Instrument **&instList, bool warmUp) {

// Logic for placing order

instList[tickData.instrumentId]->orderCount[warmUp]++;

}

//Receives market tick data and makes a trading decision

void onData(TickData &tickData) {

if (shouldBuyStock(tickData)) {

placeOrder(tickData, instrumentList, false);

} else {

placeOrder(tickData, instrumentList, true);

}

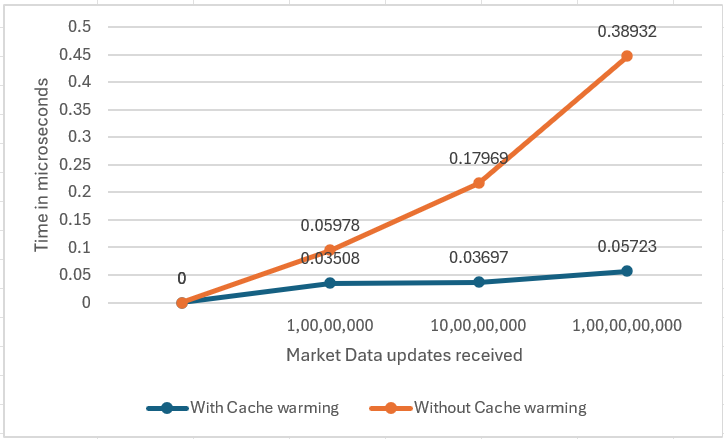

}Hence, by calling placeOrder function to warm the cache decreases the cache miss and helps in placing order faster when required. Also, by using array instead of if else block eliminates the time penalty of branch prediction. Below graph shows the latency of accessing Critical section of the code with and without cache warming:

Note: This observation is recorded on machine with clock speed: 2800MHz, L1 cache size: 32KB, L2 cache: 4MB, L3 cache: 16MB

The observations reveal that using this cache warming techniques, can significantly reduce the average time to access critical sections, thanks to preloading data into the CPU cache. This technique minimizes cache misses during actual data access, leading to faster execution times for essential operations like placing orders. To smartly fine-tune the code and leverage the benefits of cache warming, developers should consider optimizing the frequency and granularity of cache warming operations. Therefore, while cache warming enhances performance by accelerating critical data access, careful adjustment and monitoring of caching strategies are crucial for achieving optimal results in HFT systems.

Conclusion

Cache warming is a powerful technique in C++ to enhance the performance of HFT systems by minimizing memory access times. By preloading critical data into the CPU cache, HFT applications can achieve lower latency and higher responsiveness, which are essential for successful trading strategies. Proper implementation of cache warming requires careful identification of critical data and strategic use of prefetching and memory allocation techniques.